Introduction

I

am increasingly troubled by how little people seem to know--or

care--about history and context. Our current social climate encourages

partakers of social media to develop stories about other people and

about the past without questioning those stories or (even, sometimes)

collecting information. Checks against such imposed narratives--"Is that

really within your purview?" "Do you have enough information?"

"Shouldn't you find out more first?"--are often bypassed to deliver

(supposedly caring, well-intentioned, emotionally justified) verdicts,

including labels, which verdicts often go back to what I call "first

cause," a modern-day version of original sin:

I

am increasingly troubled by how little people seem to know--or

care--about history and context. Our current social climate encourages

partakers of social media to develop stories about other people and

about the past without questioning those stories or (even, sometimes)

collecting information. Checks against such imposed narratives--"Is that

really within your purview?" "Do you have enough information?"

"Shouldn't you find out more first?"--are often bypassed to deliver

(supposedly caring, well-intentioned, emotionally justified) verdicts,

including labels, which verdicts often go back to what I call "first

cause," a modern-day version of original sin:

Everything has gone wrong due to an inherent flaw in a person, plan, or social order.

Though medieval in origin, original sin didn't become a deal breaker (first cause) until the nineteenth century--the Immaculate Conception became dogma in 1854--when it was possibly brought forward not only by debates between churches but by a growing interest in psychoanalysis and scientific endeavors.

Which just proves that the nineteenth century was a very interesting time! And deserves more attention. Which brings me to The Book of Mormon.Due to the spiraling focus on

meaning-shorn-of-context, The Book of Mormon steadily seems subjected to

a kind of self-help manual approach. This approach works for some

people, and, in fairness, for much of history was a recognized approach

by believers and doubters as they used the scriptures to talk about

other stuff, including themselves.The approach lends itself to fresh and

thought-provoking dialog. It also, unfortunately, lends itself to

"since everything is relative and nobody can really know anything, you

should believe about this passage what the 'expert' or 'proper'

leader/authority/scholar tells you to believe."

That approach doesn't work for me. I far prefer context because I admire people of the past and believe they deserve to be understood as more than participants in an ideology or springboards to the reader's ego.

The context for The Book of Mormon, of course, is difficult and controversial. These posts will not address the issue of The Book of Mormon's translation. I have no investment in that argument in any direction. The primary question behind each entry is, rather, What religious climate existed at the publication of The Book of Mormon that made it such a fascinating and satisfying book to its readers?

1 Nephi 1-3: Scripture Reading

Like Lehi, Joseph Smith, Sr. was perceived

by his family as prophetic man, before his youngest son took on that

role. Whatever his role with The Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith would have

been invested in Lehi and Nephi's story. The issue of obedience is

raised since Nephi--like Joseph Smith--is rebelling against traditional lines of authority.

He is not only stepping outside the family hierarchy but outside

acceptable social hierarchies. Consequently, he takes pains to

distinguish social rebellion from spiritual rebellion. He may commit the

first by necessity—he never, he claims, commits the second. (Joseph

Smith, of course, committed both, but his family, at least, mostly

didn't mind.)

The struggle with wealth versus inspiration over the brass plates would also have struck home with Joseph Smith, who participated in the popular early nineteenth-century search for treasures and understood the survivalist's need for cold, hard cash. The history behind this trend is covered more than adequately elsewhere.

Of more interest to me is the definition of the brass plates as "spoken by the mouth of all the holy prophets..delivered unto [the prophets] by the Spirit and power of God” rather than "spoken by God...delivered as incontestable words." Bible literalism is a relatively late development in the production, collection, and canonization of scriptures. It popped up throughout the Middle Ages (and earlier), of course, but didn't take off until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The phrases "spoken by" and "delivered unto them" places the translator, at least here, on the non-literal side of the argument with the addition of a possible compromise.

Nineteenth-century readers would have been as invested in this issue as modern readers. In many cases, nineteenth-century religious communities were clearly searching for a compromise, an interpretation that could resolve difficult theological queries. Unfortunately, the issue of Bible meaning was and is often presented within the logical fallacy of either/or: One must either accept that all scriptural events are metaphors or one must accept that they are meant to mean exactly what a current translation argues, in a one word=one definition sense, without any room for debate or context (there is that word again).

An attempt to present the scriptures as being more than merely figurative or proscriptive and within a context is refreshing.

1 Nephi 4-6: The Wilderness

It helps to realize that those “fringes”--what was labeled “the West”--kept moving. At one point in the 1800s, “the West” was western New York and Ohio. It then became the Mississippi River and then what we now refer to as the Mid-West. (California became a self-described utopia and sophisticated “other” coast fairly early on—though it was also perceived as part of “the West.”)

The Gold Rush, naturally, contributed to the idea that going to the West equaled a new start, but that metaphor impacted American pioneering early on. It links back to the Puritan idea of “exodus” from a corrupt society. Methodist preachers, circuit riders, were immensely popular in the nineteenth century while their stable, elite, (well) paid, stationary counterparts on the east coast were perceived as missing the plot.Consequently, nineteenth-century readers would have reacted positively to Lehi’s decision to move his family away from perceived urban corruption into a potentially dangerous wilderness. And the thread of violence that inhabits these chapters would have made more sense to nineteenth-century readers than it often does to modern readers. The “Wild” West was truly “Wild” in some cases and the attitude “better left alone so take care of themselves” from many governments, including the Federal government (pre-Civil War), was prevalent.

Although indigenous people and trackers and traders saw the wilderness as an approachable and useful setting, the underlying mindset for newcomers was:

One goes into the Wilderness and dies heroically (or becomes a hermit--see Saint Anthony--and dies sacrifically) or one goes into the Wilderness and fights off all contenders.

The tensions here between freedom and organized leadership, pacifism and violence continue through The Book of Mormon. Nineteenth-century readers could relate.

1 Nephi 7-11: The Tree of Life

Lehi’s vision of the Tree of Life followed by Nephi’s personal vision of same.

More than anything else, these chapters would have connected to the intense individualism of American thought in the nineteenth century.

This is the era of de Tocqueville, who arrived in the United States and observed separation of church and state in action. “Good golly,” he exclaimed (I am summarizing), “when religion is not imposed by the state, people are, what do you know, more religious!”The American Revolutionary was also a lingering narrative of intense individualism—rebellion against (or exodus from) the corruptness of the Old World. Even Puritan thought, which now strikes modern people as rather dictatorial, was about individual salvation, a single person coming to understand God’s grace through lifelong, intense personal analysis.

It is difficult to entirely capture—we are products of the early C.E. era, after all—the break here from communal sin and suffering that encapsulates social orders in antiquity. That urge remains, of course, what with Witch Trials and their modern equivalents: one bad apple rots the entire barrel! Twitter appears to be the ultimate expression of badgering everyone everywhere into some kind of compliant order.But even Twitter is the product of individual offerings.

Individualism existed in antiquity and forms the basis of most narratives, but the social order—and therefore the social role—of populations was entirely presupposed. Kings were not scribes. Scribes were not peasants. Peasants weren’t anybody. If the king is saved, you are all saved. Might as well get on-board.

The Common Era concept of the individual as agent, who works out an individual salvation, is something that nineteenth-century readers would have entirely comprehended and embraced and that modern folks rather take for granted, even when they criticize the ideology.

Lehi’s Tree of Life rests on the premise of the individual agent. Although the “strait and narrow” path connotatively gives rise to images of intolerance and exclusivity, in Lehi’s dream it is a path that each person must walk alone, even if there are others ahead and behind: each of Lehi’s children and even his wife are referenced separately. The path is a person’s integrity or personal path in life—choice of profession, artistic endeavor, prophetic calling (see Joseph Smith)—whatever self-definition a person embraces and endures and sacrifices for. The “great and spacious building”—on the other hand—is the ultimate collective. People get there individually but they stay in the “safe” Borg-like “in-group” that mocks individuals and scorns the difficult pathway that each individual treads.Consequently, the “great and spacious building” houses detractors, sneerers, people who love labels, mockers, revilers, obnoxious cliques—those who prefer to watch others drown rather than make a life for themselves. (All members of the great and spacious building point in the same direction, as a mob would.)

There are other possible interpretations, of course, including the search for a single path to God’s grace, a search that was also dear to the Smith family. Although communal living was all the rage, nineteenth-century readers still would have perceived such a search in individual terms, one that this group, this community carries out for the sake of each member. (Despite the Donner party haunting American mythology, most successful pioneers moved west within specific groups—religious groups, town groups, family groups.)

And few nineteenth-century readers would have balked at the fruit of the tree being happiness, love, and joy (as opposed to discipline, humiliation, and subjugation). Gotta love those Americans and their life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness mindsets! (Even the Puritans perceived the happiness and beauty of nature as the key to comprehending God’s grace.)

When I was growing up, there were still church members who saw the Catholic Church as the “Great and Abominable Church” (I grew up in upstate New York, so our congregation included ex-Catholics).

That is a far less palatable idea now, of course, and I got tired of

it early on. Although some members liked to blame the Great Apostasy on

the Council of Nicaea, it was obvious from reading the scriptures and

history that (1) any apostasy within the early church occurred within that early church well before the end of the first century C.E. (See all of Paul's letters.)

What would nineteenth-century folks have thought about the phrase?

Well, actually, they would have associated the “Great and Abominable Church” with Catholicism. And the narrative of Chapter 13 lends itself to that interpretation (though not entirely).

Although the Reformation was nearly 300 years old at this point, it

was still fresh in the American mind. Puritans left England due to

persecution from the remnants of Catholicism, Anglicanism in the form of the Church of England. Europe was still a

bastion, in the American mind, to Catholic influences. Truly radical

Protestantism, went the thinking, couldn’t take root until the supposed

stain of Catholicism was wiped away. This attitude lingered well into

the twentieth century.

It is to Joseph Smith’s credit that he didn’t get caught up in going after Catholics specifically, which a number of pundits and muckrakers of the time did (see Awful Disclosures above). It’s unlikely that he knew any Catholics anyway. But the man also thought in analogical terms. Like Paul with paganism, Joseph Smith’s overall writing is more focused on underlying causes of pride, such as fancy education and wealth and close-mindedness re: the Congregationalists that he grew up around, than specific doctrines or history.

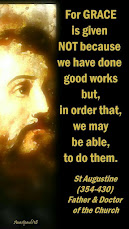

1 Nephi 14-22: Grace & Works

The

Book of Nephi begins a struggle over hell and grace and punishment that

continues throughout The Book of Mormon. It was an ongoing struggle in

the nineteenth century as well as today! That struggle is arguably part

of the human condition.

Nineteenth-century readers would have had personal contact with this struggle, being familiar with Arminianism—God’s grace is universal—and Calvinism—pre-ordination of salvation. In America, the struggle came down to Methodism versus what had become by that time Congregationalism (the latter term now has a broader use).

On

the one hand, hell as punishment is a given. However, in Nephi’s

interpretation of Lehi’s dream, the quality or character of hell is

defined: “And I said unto them that the water which my father saw was

filthiness; and so much was his mind swallowed up in other things that

he beheld not the filthiness of the water” (1 Nephi 15:27, my emphasis).

On

the one hand, hell as punishment is a given. However, in Nephi’s

interpretation of Lehi’s dream, the quality or character of hell is

defined: “And I said unto them that the water which my father saw was

filthiness; and so much was his mind swallowed up in other things that

he beheld not the filthiness of the water” (1 Nephi 15:27, my emphasis).

Although the passage about hell may seem rather harsh—and a bit skimpy on the grace side—nineteenth-century readers would have seen it as bolstering the idea of universal grace: hell is not the place where people who didn’t complete all the correct rituals or joined the right congregation go (it isn’t group-identity hell). It isn’t a place where people go whether or not they worked hard not to go there. It is the place where individual “filthy” people go.

Religious designation is not a qualifier. Neither is race. Neither is birthright. This perspective would have been perceived in the nineteenth century as provocative. (Readers are being prepared for a complete rejection of infant baptism.)

2 Nephi 1: The Promised Land

It is a difficult idea, in part because it has, to an enormous degree, been disproved by historians. The fall of Ancient Rome, for instance, was classically blamed on the sinful decadence of the later emperors (see Gibbon). A monk in England’s Early Medieval Age, Gildas, likewise blamed the conquest of England by Anglo-Saxons on the sins of the residents left behind when Rome withdrew its military protection.

But Rome actually survived (as in, continued to last longer than the United States has currently been around) appalling behavior by appalling emperors who were degeneracy personified. There were many more factors involved in Rome’s decline, including plague and, oh yes, “barbarians.” (It’s not as if Asterix et al. changed their minds about self-governance one morning because “Oh, now, the Romans are behaving righteously.”) And Rome is arguably still limping on today. The Anglo-Saxons did not in fact invade. They more likely arrived in England slowly over time as settlers. And since the Anglo-Saxons had pretty much all converted to Christianity by the tenth century, it is hard to see (now) what Gildas was complaining about.

On the other hand, unrighteous behavior makes it harder for a group to cohere—trust—build a coalition (see C.S. Lewis’s hell in The Great Divorce, in which residents move further and further apart), making it harder for that group to come together to stave off invaders. Likewise, in a merit-based culture, the argument “sin=bad results” makes some sense. People earn their positions in life.But a merit-based culture focuses on the individual as opposed to the group: what the individual has stupidly done—like drugs or embezzlement—can explain where that individual ended up. So sure, bad things happen to bad people. But bad things also happen to good people. And good people do dumb things. And good things happen to bad people.

And…I could keep going.

From a nineteenth-century perspective, 2 Nephi 1 is an explanation rather than a condemnation (though the premise of the explanation can lead to circular, begging the question illogical condemnation). The Native Americans were obviously struggling as they were increasingly pushed to the margins of the American landscape. Why? A common explanation in Protestant America for anybody’s struggle/demise, which still exists in religious and non-religious discourse today:

Somebody must have sinned in the past!

The more interesting point, to me, is that this explanation/perspective is almost instantly qualified—and will continue to be qualified—in The Book of Mormon: “for if iniquity shall abound, cursed shall be the land for their sakes, but unto the righteous, it shall be blessed forever” (2 Nephi 2:7, my emphasis).

The central idea here—people are drawn to what they themselves

create and desire and pursue—will come up again and again and again.

This point of view is blessedly uncommitted to the idea that God uses

nastiness to further His aims. People make out of the world their own

heavens and hells.

The implications of the argument, I would argue, were not lost on the translator.

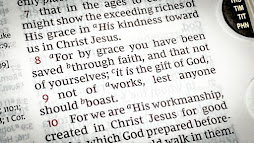

2 Nephi 2: Grace & Works Again

As mentioned earlier, The Book of Mormon continually tackles the problem of hell, grace, works, and damnation. More on grace & works will follow. However, 2 Nephi 2 deserves to be mentioned upfront.

In 2 Nephi 2, an answer to the grace-works problem is proposed with startling clarity. From a nineteenth-century perspective, it would have been both familiar (innocence and rebirth were common tropes in American discourse) and highly unusual:

- "Salvation is free" (2 Nephi 2:4).

- Agency is defined as "to act for themselves and not to be acted upon" (2 Nephi 2:26)—the purpose of the Atonement to preserve agency is introduced.

- "Adam fell that men might be, and men are that they might have joy" (2 Nephi 2:25).

In the 1800s, the last line was a direct contradiction of the classic

view of Eden and Adam’s fall as linked to original sin. With the Book of Moses,

Joseph Smith would directly tackle the Garden of Eden and entirely

remake its purpose and consequence. The fundamental change here is one

of the doctrines that will make Mormonism a “restorationist” religion rather than a religion in the classical Christian tradition.

2 Nephi and Jacob: Grace & Works Background

2 Nephi and Jacob: Grace & Works Background

2 Nephi and Jacob delve into grace and works.

Two problems underscore much religious discourse. Nineteenth-century Christians in America grappled with them directly:

- The problem of grace versus works—that is, the problem of a deity's mercy versus human merit.

- The problem of the elect or elite, those who supposedly deserve God’s mercy and intervention.

At this point, I will turn to etymology—then I will return to the nineteenth century.

In James’s statement, “Faith without works is dead” the word “works” is based on a Greek word, ergon, which refers to “energy.” The word is connected to the business of agriculture and trade—that is, it is connected to multiple roles that people may take in a community. (I did not know this background information for myself: see this site here.)

That is, faith without energy is meaningless because faith without energy means a person is dead.

We wake up in the morning. We get out of bed, feed the cats, carry out jobs, open mail. Everything is something we do as living people. And during all of that, we ponder stuff, which arguably is also an action in which neurons leap the boundaries between synapses. Faith is, in fact, ongoing agency, a position that The Book of Mormon has already committed to doctrinally.

However, by the time the Protestant Reformation was in full force, “works” no longer meant “the decisions I make everyday about my life” or, even, “charity” (which is the context for James). It meant what John McWhorter references when he talks about “performances” by so-called protesters. Since they aren’t protesting anybody who dares to disagree with them—and the so-called authorities applaud them (and sometimes feed them)—and their protests rarely, if ever, end with an actual sacrifice of privilege (few higher educators are giving up actual offices or jobs), much less the adoption of a differing lifestyle—they are, in essence, showing off.That is, “works” as defined by Martin Luther et al. became actions that by themselves don’t appear to have a moral component but have been turned into a moral necessity: good people jump through these hoops; use these phrases; perform these routines; makes these mea culpas.

The issue becomes complicated because not all rituals are meant to be works. Sometimes, they are meant to be reminders of faith or inductions into cultural belonging. A signal of commitment.And Protestants rapidly split into those who despised all rituals, including any custom that took place in any church or within any religious group, and those who said, “Uh, you folks are kind of throwing out everything at once.” (Forensic anthropologists are not very happy with Protestant zealots in England who threw out Anglo-Saxon saints’ bones that can now not be tested.)

See the posts Why Choosing the Supposedly Correct Side is Difficult.

To nineteenth-century American readers, “works”—on the one hand—smacked of Catholicism and the corrupt Old World and stuff like worshiping saints. On the other hand, early Protestantism almost immediately created its own sets of “works.” Good religious people embrace the following lifestyle and use the following language and support the following celebrities/political causes…

And the truth is, every culture, by the nature of being composed of non-dead and human people, is going to have “performances,” stuff that people do because that’s part of being a member of a community. (We even create “performances” in our personal lives/routines.) If we decide that only “meaningful” actions should be carried out, we run the risk of ending up as humorless as, well, a bunch of Woke Puritans who burn Maypoles, close down theaters, get offended over single words and phrases, and lecture others on supposedly bad thoughts.

Joseph Smith was not a guy who lacked a sense of humor.

In opposition to “works” is the principle of grace. Saint Paul argues that we are saved by grace. Full stop. Not “after all we can do.” We are saved by grace. Propitiation is off the table. God doesn’t bargain. And humans aren’t meant to be grifters. Give it up.Yet even Paul struggled with the reality of communal living and the irritation of people doing petty things like, say, suing each other. And he also had a sense of humor.

In

sum, if one sets aside the "performance" side of works, the issue of

grace v. works/action/energy still remains: Do humans earn God's

attention? Or does God offer attention? Does God react based on merit?

Or is merit human wishful thinking?

God is bigger than us and can do what He wishes, so we are saved. But sometimes people are jerks. And sometimes they walk away from God. And sometimes they think they have walked away but they haven’t. And sometimes they think they haven’t but they have. And how fair is it really for a jerk to be saved? (According to Jesus Christ and the parable of the workers, Entirely fair and so not your business.) And since we do get up every morning and do stuff, shouldn’t that stuff be moral? And if we claim to love God, shouldn’t there be a connection between that love and the moral stuff we do?

Do we work our way towards the infinite by a checklist? Or by learning and growing? Or by being loved and accepted?

I consider Christianity one of the most fascinating religions on record simply because it hauls this problem to the surface and doesn’t fully answer it.

The Book of Mormon and its translator, for instance, will return to the

problem over and over again. Why not? The Book of Mormon’s initial

readers were struggling with it as much as Paul’s audience and modern

believers.

To be continued…

No comments:

Post a Comment