The issue of fairness begins with resurrection.

Nineteenth century readers were heirs to Calvinist concerns about resurrection (the Calvinists produced a disproportionate number of papers and sermons compared to the rest of the American colonies—their impact on religious thought was as great as it feels).

When

exactly did people resurrect? Some Calvinists believed that they had

already resurrected; the change began or definitively occurred with

conversion. (Calvinist debate over when precisely conversion

takes place could fill several tomes. See below.) Others maintained that a First Resurrection would take place around a Millennium.

First Resurrection, which postulates that the righteous will resurrect prior to the Final Judgment, was common currency in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries. Alma 40:15-18 addresses the "first resurrection" while directly refuting that resurrection refers to a state of mind. According to Alma 40,

- The Resurrection is not abstract.

- Everybody is resurrected (Alma just isn’t sure when).

- There

is a time of purgatory, what Tibetan Buddhists refer to as the

Intermediate Existence (the concepts are not exactly the same and not

exactly different).

Nineteenth-century readers must have found such clarity a relief. Calvinist debates on the topic had reached bizarre levels of metaphysics, which seems to be a tendency in all religions, abstracting the material world into “meaning” rather than facing its actuality.

With Calvinists, the problem arose in part because they couldn't square the reason-based arguments of the Enlightenment, what they currently

understood about the body after death, with theology. (They didn't know about DNA.)

Paul

warned the philosophizing Greeks that any type of physical

regeneration/reality would prove a “stumbling block” and it did—to the

Greeks and to the Mahayana in Buddhism who presented the idea of

"mind-only...a form of idealism which sees consciousness as the sole

reality and denies objective existence to material objects" (Keown).

Physical resurrection implies at least two realities that elites within various religions have found unsettling: experience is more important than a feeling of conversion or a set of “known” beliefs; progress is contingent on a physical body carrying out its agency (rather than "performing" certain tasks as markers of salvation).

Joseph Smith--and his successor, Brigham Young--stuck to a physical restoration/heaven. In many ways, Joseph Smith was attempting to recreate the Calvinist New England covenant society in its person-to-person reality--without all the stuff he didn't like.Many of his followers felt the same.

Yes, says Alma 41, salvation is contingent on behavior.

Except the dissonance of a loving yet punishing god--which troubled nineteenth-century believers--is immediately qualified and transformed in Alma 41 and Helaman 14:30-31. In Alma 41, judgment becomes about "restoration" or, to borrow from Buddhism, the result of "actions driven by intention." Where a person ends up is contingent on behavior because behavior (or works) indicate "[one's] desires of happiness or good" (Alma 41:4-5).

Buddhism entertains the same tension over intention, behavior, and results: Isn’t performing good deeds just a checklist? Can it really ever lead anywhere? Round and round and round we go...Early on, Buddhists determined that more was needed. Virtue, sure, but also wisdom.

Any teacher can point to the difference. The student who has produced an essay isn’t in the same state/condition/learning as a student who understands how and why and when to produce an essay. The same problem underscores all human endeavors. Are people just performing monkeys (put enough monkeys in a room with typewriters...) or are they learning and growing and developing in individually unique ways?

Likewise, in The Book of Mormon, the solution to the problem of merely virtuous behavior--checklists--is to go beyond that checklist to character: What type of person have you become? What do you care about? What will you be drawn to? What will accrue to you? Where will you automatically sort yourself?Joseph Smith likely would have been accused of antinomianism (again, everybody in early America was) when the book he produced declared,

"Behold, ye are free; ye are permitted to act for yourselves" (Helaman 14:30).

The caveat that follows, "wickedness never was happiness," is not, in fact, a punishing or warning phrase. It is part of a larger argument, an argument which occupied nineteenth-century theologians:

How fair is God? Really?

WickednessTwo issues dog the problem of wickedness: 1) What is wickedness? What if cultures, religions, time periods don’t agree on the definition of wickedness?

From my perspective, there is surprising agreement throughout history on the basic notion that harming people (unfairly) for personal gain is wrong.

2) Just because behavior upsets humans does that mean it upsets deity?

|

| Nathan assumes a standard |

| of "good" before God when |

| he calls out David. |

Nineteenth-century preachers were well-aware of both issues. They increasingly used “natural law” alongside the Bible and the Holy Spirit to define “wickedness” and the expectations/character of God. Antinomianism immediately showed up (again) since feeling the holy spirit is an entirely personal and non-pin-downable event (which didn't stop people from trying to pin it down).

“Natural law" was also somewhat suspect, but it could apparently be reasoned out using philosophy and observation. The Bible was supposedly clear except (a) the Bible’s clarity was being challenged by German scholars; (b) not every theologian agreed on the Bible’s meaning—an increasing number pointed out that Saint Paul was probably speaking hypothetically or metaphorically or specifically or historically when he spoke about “election.”

A few theologians pointed out that whatever the “truth,” it wasn’t up to individual people to decide whether or not that truth was palatable or how it works. And frankly, these theologians had Jesus on their side since he delivers several parables with the rider that judgment is not up to anybody but God.And a few theologians, like Joseph Smith, went the mythic route: what is the STORY of God, heaven, hell, and the afterlife?

Still, a great many theologians in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries were extremely fascinated by the anatomy of salvation--its inner workings--and opinions about those workings did have observable results in the day-to-day social order, as in, Who comes to church? Who ought to come to church? Who should be accepted into the church? What does membership look like? If members are judged, why are they judged?

For Calvinists, membership often came down to a moment of “true” conversation. But what IS a moment of “true” conversion? How is it brought about? What does it look like?

One approach in New England Calvinism to separating the good from the bad (saved from the non-saved, elect from the non-elect) was to define a believer’s moment of “true” conversion (keep in mind: not all Calvinist theologians thought that figuring out “true” conversion was necessary). And the way to define that moment was…To scare the snot out of people.

I’m not kidding! It wasn’t hellfire and brimstone cloaked in “better you than me” self-righteousness. It was “you better feel that hellfire and brimstone—we all have—and you must before you can take the next step.”

People had to be frightened in order to undergo a conversion. The Amish concept of shunning is in line with this idea: that an individual must be horrified NOT in order to be scared into compliance but to be scared into a full realization of the actual state of their souls.Compliance versus realization may seem a distinction without a difference--but in fact, when tied to its theology, this awareness or awakening constitutes a distinction. Jonathan Edwards' Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God aimed at this idea: once you have a catharsis of how sinful you are, then you will wake up (witness the behaviors and attitudes of modern protesters):

O Sinner! Consider the fearful Danger you are in: 'Tis a great Furnace of Wrath, a wide and bottomless Pit, full of the Fire of Wrath, that you are held over in the Hand of that God, whose Wrath is provoked and incensed as much against you as against many of the Damned in Hell: You hang by a slender Thread, with the Flames of divine Wrath flashing about it, and ready every Moment to singe it, and burn it asunder; and you have no Interest in any Mediator, and nothing to lay hold of to save yourself, nothing to keep off the Flames of Wrath, nothing of your own, nothing that you ever have done, nothing that you can do, to induce God to spare you one Moment.

As Edward Ingebretsen, S.J. points out in Maps of Heaven, Maps of Hell: Religious Terror as Memory from the Puritans to Stephen King, horror in America has very deep roots.By the end of the eighteenth century, scaring true conversion into people was running up against competing/contradictory ideas: (1) God wants humans to be happy; (2) God loves humans and doesn't threaten them.

And Jonathan Edwards did believe in a God of love. The effort of late Calvinists to square evidentiary proofs from scriptures, beliefs in happiness, and respect for beautiful nature with a God who (still) scares the snot out of people explains...a great deal about late Calvinism.

Nineteenth-century readers would have been exceedingly familiar with the horror version of Christian "awakening" (which, again, was conflicted since it existed side by side with personal, positive spiritual outpourings). Consequently, nineteenth-century readers would have recognized the purpose of Jacob's passage:

And according to the power of justice, for justice cannot be denied, ye must go away into that lake of fire and brimstone, whose flames are unquenchable, and whose smoke ascendeth up forever and ever (Jacob 6:10)

And they would have recognized the doctrinal concept presented in Alma 42:16:Now, repentance could not come unto men except there were a punishment, which also was eternal as the life of the soul should be, affixed opposite to the plan of happiness, which was as eternal also as the life of the soul.

Just about every part of the above passages will be heavily qualified by Joseph Smith at a later date, starting in Doctrine and Covenants 19 in which "endless" punishment is clarified as referring to God's punishment, NOT to a punishment without end. Three kingdoms of glory (Doctrine and Covenants 76) will later further qualify the idea of endless or eternal punishment/damnation.

Wickedness and punishment occupied nineteenth-century religious minds. Both issues come back to the problem of fairness: Would God have set us up to fail? The conundrum is more than “why does evil exist?” becoming “why does evil exist within humans?” Original SinIt existed early on, of course. Saint Augustine struggled with it. However, generally speaking, the more orthodox believers in the early church sided against the nastier aspects of Gnosticism: the physical was NOT inherently evil, corrupt, bad, disgusting; Christ being born as human didn’t automatically make him not-God. Christian thinkers quite early on propounded the image of a loving God who did not side with the devil against humanity and humans who could choose right from wrong. One’s birth might be a matter of fate but, as Shakespeare's King Henry states, “Every subject’s soul is his own."

Calvinism in America threw itself into the deep end by wanting to apply fate to people's souls beyond birth while

embracing free will as well as rational explanations for stuff. And one

of the easiest rational explanations (on the surface) has always been

to figure out who is to blame.

Adam as the guy at fault (humanity would be so happy if only Adam and Eve hadn’t…) was omnipresent enough as a theological argument in the nineteenth century for the 3rd Article of Faith (written down by Joseph Smith and his early followers) to state, “We believe that men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression.”

Because, of course, blaming Adam didn’t really help matters either since, as mentioned earlier, Why would God allow Adam’s fault to impinge on us? Why would God set up humans to fail? Why would he give them natures that couldn’t get better? How far does grace go to wipe all that out? Is it fair to override people’s bad actions? Do murderers go to heaven? Well, why not? Doesn’t God want humans to be happy? (Happiness is a big issue in the nineteenth century.)

Joseph Smith’s approach is to do the following:(1) Take free will to its logical conclusion: in sum, the whole point of life is for humans not just to have free will but to exercise it as a reflection of each human's individuality (to be "agents unto themselves");

(2) Negate the idea of inherited sin and define sin as contingent on knowledge (hence, all children are saved);

(3) Distinguish between “sin” and “transgression.” Adam and Eve didn’t yet know good from evil so they transgressed when they ate the fruit; they didn’t sin. They left the Garden of Eden because they needed to go. As mortal beings, they did eventually sin. But they weren’t inherently corrupt and neither are we. Messing up is normal. God already figured that out.

Hints of the above approach appear in Alma 42.

Alma 42 first addresses antinomianism, likely because it is about to present what others would call antinomian arguments. So it first argues that God is just (fair) and consistent. Mercy can't override justice. It goes on to present in outline, material that will appear in the Book of Moses, presented by Joseph Smith in the 1830s. In Alma 42,

- Adam and Eve become “as God,” knowing good from evil.

- They are “sent forth” from the presence of God, so they will die physically, which requires (“it was expedient”) a universal resurrection.

- They are separated temporally and spiritually from God, which requires an atonement.

- Sins arise from specific decisions made by individuals as they, expediently, “follow after their own will"—not from God’s punishment.

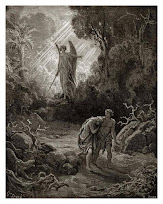

|

| A VERY Mormon view of Adam and Eve |

“And now,” Alma writes his son, “I desire that ye should let these things trouble you no more” (Alma 42:29).

When Joseph Smith can side with actual reality over theory, he usually almost always does. After all, telling God who and when and why He can save is completely unnecessary. And possibly blasphemous.

On the other hand, having a story about God (myth = story; theology = argument in a positive sense) does influence HOW people carry out their beliefs in actual reality. Joseph Smith splits the difference.

No comments:

Post a Comment