Thanks, Mom for supplying the biographical evidence for the 1946 spectator. There are many perks to having a family which can, and will, produce primary source material from the last hundred years or so. This is one of them.

*****************************************************

The Duchess of Malfi

If truth-in-advertising principles applied to the

titles of 17th-century plays . . . [the] current production

would be called something like

"The Guy Who Did In the Duchess of Malfi

and Then Felt Bad About It."

New York Times reviewer of a 2003 performance

If truth-in-advertising principles applied to the

titles of 17th-century plays . . . [the] current production

would be called something like

"The Guy Who Did In the Duchess of Malfi

and Then Felt Bad About It."

New York Times reviewer of a 2003 performance

The Duchess of Malfi by John Webster did not arrive in America until nearly 200 years after its birth. Unlike Shakespeare's plays, it was not performed in the colonial era or published by eighteenth century American presses. Nor does it appear to have entered the colonies in chapbook form. The play was first performed on Broadway in 1858. For the next 100 years, it lurked in the cultural mainstream; it was referred to in book reviews and magazine articles; discussed on radio and television. Through the 1970s and '80s, the play faded until now it is performed only occasionally in off-off Broadway productions.

The Duchess' arrival in America was contingent upon certain cultural conditions--fascination with Shakespeare in the mid-nineteenth century; the middlebrow approach to classics in the 1940's. During the mid-twentieth century, it became a vehicle for an ambitious, Hollywood-oriented star. It was advertised as a thriller in the age of film noir and detective novels. It continually failed in the theatre, yet was continually revived. Through votary theory, we will hopefully reach an understanding of how 1940's audiences might have dealt creatively with The Duchess--how they might have positioned themselves within its performance.

The Play's History

John Webster wrote The Duchess of Malfi in the early part of the seventeenth century. It was performed at the Globe Theatre between 1613 and 1614 and printed in 1623. Although Shakespeare and Webster overlap, Webster has always been attached, by scrupulous critics, to the Jacobean era. This is fitting since unlike the heroic pageantry linked with Elizabeth's reign (and at work in Shakespeare's earlier plays), the Jacobean era possessed a darker caste of mind. Many of Shakespeare's more problematic, less definable dramas--Othello, All's Well That Ends Well, The Tempest--were written after James I began his reign.

The Duchess commences with two brothers confronting their widowed sister. They wish her not to marry again--partly out of greed (they don't want her fortune to pass into non-related male hands) and partly from sheer cussedness. One brother is a corrupt Cardinal. The second is a high-strung Duke who will later repudiate and mourn his sister in the same breath. The Duke leaves his henchmen, Bosola, in the Duchess' service. Bosola discovers that the Duchess has taken a lover--she bears three children in the course of the play--but fails to discover the lover's identity until the Duchess reveals it to him under the misapprehension that Bosola is a friend. (There is more than a hint of Iago in Bosola's character.)

Her lover--or husband, depending on how seriously you take their marriage vows--is Antonio, her steward, a man of Bosola's class. Bosola is impressed by the Duchess' choice, but he too is a faithful servant (unlike Iago, he does not serve himself) and reports the Duchess' conduct to her brothers. They take immediate revenge, banishing both the Duchess and Antonio from Malfi; they later seize the Duchess and her two youngest children, returning her to Malfi under house arrest. The Cardinal leaves the issue there, but the Duke is incestuously obsessed with his sister. He tries to drive her mad; that failing, he orders her execution, which Bosola oversees. The Duke then repents his order, and Bosola, who was never keen on the murder to begin with, takes his revenge on his perfidious employers (they haven't paid him). He kills the Duke and the Cardinal. A number of other people, including Antonio, die along the way.

It is a macabre play and on paper (and, unfortunately, occasionally on stage), it appears melodramatic in the extreme. One scene of The Duchess contains three dead bodies onstage with three (newly killed) offstage. To hear the play read gives a better sense of its grandeur. The poetry rumbles. The action builds in tension, becoming darker and more disturbing as the Duke descends into madness and the Duchess' life disintegrates. Webster ably weaves together disparate characters, themes and outcomes. There are a tad too many deus machinas, and Webster's vision of humanity is depressing. The play is full of bitter comment over the corrupt nature of the Church and governments. Bosola, however Iago in appearance, is more honorable than Shakespeare's villain; he is the only character in the play who faces the reality of himself. Even the Duchess--noble, defiant--reacts more than confronts.

The play was performed in England throughout the seventeenth century. Samuel Pepys saw it twice.(Footnote 1) Webster was never as popular as Shakespeare or Ben Jonson, but The Duchess underwent three printings, and poets and critics praised Webster's talent. However, unlike Shakespeare, none of Webster's works entered America during the colonial era, either in print or performance.(Footnote 2) In England, The Duchess underwent expurgation and revisions (the unflagging pastime of eighteenth and nineteenth century sentimentalists) in order to emphasize the romantic subplot. It was revived spasmodically. A cut version was finally produced on Broadway in 1858.(Footnote 3)

Published versions of the play were available to Americans in the late nineteenth century. The Dramatic Works of John Webster, edited by William Hazlitt, was published in 1857 and a Temple Dramatists edition of The Duchess in 1896. Both were published in London and surfaced in America. California's Overland Monthly magazine referred to the Temple Dramatist edition (a small, pocket size book) in 1897 with the aside that Webster's plays would be "marvels of dramatic art" if it wasn't for the inevitable comparison to Shakespeare.(Footnote 4) The play itself was referenced in several articles between 1871 and 1889. All articles highlighted the Duchess' dignity and courage in the face of impending doom.(Footnote 5)

It is difficult to gauge The Duchess' prevalence in America in the early part of the twentieth century. In 1919, a theater correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor, reviewing a London revival of The Duchess, felt it necessary to outline the plot for his American readers. (He also compared Webster to Shakespeare.)(Footnote 6) The Mercury Theatre in New York considered The Duchess for its 1938 season before changing its mind in favor of Heartbreak House. The play was performed by a college group in 1945 and a repertory theater in early 1946.(Footnote 7) It may yet have remained an obscure footnote, one of those many annotations necessary to textual exegesis, had not the play been revived on Broadway in 1946. It had been produced recently in London, starring John Gielgud as the Duke, to great acclaim. Bertolt Brecht and W.H. Auden wrote an adaptation for the Broadway production (again, it was cut), although a prior adaptation was eventually used instead (Auden's name remained in advertisements for the play).(Footnote 8) Elisabeth Bergner played the Duchess. Her husband, producer/director Paul Czinner, hired British director George Rylands (he had directed Gielgud's production) as well as British composer, Benjamin Britten for the overture and incidental music.(Footnote 9)

The play premiered in Providence, Rhode Island in late September 1946, moving to Boston and on to the Barrymore Theatre in New York where it lasted for approximately a month, thirty-eight performances in all. During the same time period, 1946 playgoers could have attended State of the Union (1946 Pulitzer Prize play), Denes Psychodramatic Theatre's 6 Dramatized Case Histories and the unending Life with Father (the season's hit at 4,066 performances).(Footnote 10) Despite The Duchess' low number of performances, the production does not seem to have hurt the careers of any of the actors, although Bergner never did make the break into Hollywood.(Footnote 11)

The next major production occurred in 1957 when The Duchess ran for three weeks at the Phoenix Theatre. In the last fifty years, the play has appeared on radio and television, in novel form, and in off-Broadway productions.(Footnote 12) Since the 1990's, productions have been darker, more psychological and less likely to leave out the incest; Bosola (the Iago character) moves definitely center stage. The play is rarely read, although the Norton Anthology included it in editions, after Norton's 1962 debut volume, to represent Jacobean Playwrights. (A bell-tolling indication, if one was needed, of The Duchess' waning popularity.) More recently, the play appeared as the sub-plot of the arty horror film Hotel, in which a largely American cast strives to film The Duchess (cut to make it more "accessible") in Venice. They spend their evenings at a hotel of psychotic wait staff; the staff is managed by an ironic maitre d' who, like the misogynistic Bosola, considers the Duchess "a whore."(Footnote 13)

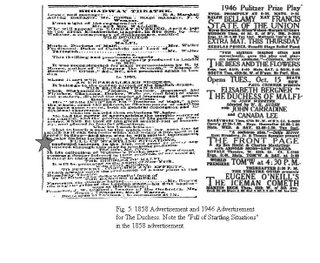

Treatments

TreatmentsTreatments of the play have varied over time, although there are consistencies between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The twentieth century shared with the nineteenth an appreciation of Webster's connection to Shakespeare, a belief that the Duchess was the central character of the play, and a proclivity for cut scripts. For its first production on Broadway in 1858, the play was advertised as a Shakespeare clone--"upon the whole [Webster's White Devil and The Duchess of Malfi] come the nearest to Shakespeare of anything we have upon record," stated the advertisement. "Startling situations" were promised as well as a "Dancing Barber" after the show.(Footnote 14) It sounds preferable fare to the 1946 production which was advertised blandly as "Elisabeth Bergner in The Duchess of Malfi by John Webster/ Adapted by W.H. Auden with John Carradine and Canada Lee."(Footnote 15) John Gielgud had recently made the play a sensation in London (as Ferdinand the Duke), and reviewers assumed Czinner chose The Duchess as a promotional tool for his wife Bergner's talents. At the time, Broadway was the center of the entertainment industry, and doubtless it was hoped that a stunning performance (by Bergner) would translate into a Hollywood contract.

Overall, the reviewers disliked Czinner's production. The actors were praised individually, but the play failed to live up to the reviewers' expectations. Most were familiar with Webster's drama and had anticipated "bombast and fustian" (as one reviewer described it) or, at least, some blood-thirsty horror.(footnote 16) The play does, after all, contain multiple murders, a severed hand and strangulation. Czinner's production didn't deliver. Edwin F. Melvin of the Christian Science Monitor compared the Boston opening to a prior stage version, noting, "It telescopes the remaining events and disposes of [the Duchess'] villainous brothers Ferdinand and the Cardinal and their henchman, Bosola, more rapidly than even Webster contemplated." He then praised Bergner for a "quality of emotion lacking through much of the evening," a rather backhanded compliment.(Footnote 17) Brooks Atkinson of the New York Times was also disappointed, calling the production "conventional," "tepid" and "too genteel." Nine years later, he still wasn't happy. The 1957 production of The Duchess at The Phoenix Theatre was advertised as an "Elizabethan thriller by John Webster" but the production struck Atkinson as "studied," "elaborate, formal and contrived." "If Webster is not sensational," he explained in his review, "he is nothing."(Footnote 18)

Yet it is Webster's sensations that evidently bothered the play's producers. Preceding the 1957 production, a discussion took place at The Phoenix entitled "'The Duchess of Malfi.' Penny Dreadful or Poetic Tragedy?" a topic that reflected the middlebrow concerns of the day. (The Duchess and Antonio attended; since the murderer, Bosola, wasn't included, the discussion was likely weighted towards "poetic tragedy.")(Footnote 19) The question was evidently still a concern in 1962 when the McCarter Theatre Company presented The Duchess as part of their "Shakespeare And His Contemporaries" season. The positive review praised the play's lack of "excess" which did not "turn [the deaths] into condescending sport."(Footnote 20) The impression is one of slight tedium. Where, Brooks Atkinson would have asked, are the "startling spectacles"?

For "startling spectacles" abound in The Duchess. The play contains a mistress-ridden Cardinal; an incest-ridden brother; a secret lower-class lover; three secret pregnancies; an ambiguous, murdering thug who has all the best lines and lives longer than the heroine; the aforementioned severed hand; seemingly dead bodies made out of wax; plus, "real" dead bodies littering the stage. The Duchess has always tipped on the edge of melodrama and with so many bewildering possibilities, the safest interpretation may be a specific one. The favored interpretation in 1946 and previously was the Duchess' courage in the face of her own death. Sure, she snuffs it, but she does it with style. (Bette Davis accomplished this, without the severed hand, in the 1939 film Dark Victory.) It is the Duchess who tells Bosola, "I know death hath ten thousand several doors/For men to take their exits, and 'tis found/They on such strange geometrical hinges/You may open them both ways.--Anyway, for heaven sake/So I were out of your whispering," which translated means, "So I'm going to die; stop going on about it already."(Footnote 21)

This interpretation of nobility in the face of death, common also in the nineteenth century, was perpetuated in the early twentieth century by the promotion of middlebrow culture: what Lawrence Levine, among others, calls the "sacralization" of culture and Joan Shelley Rubin, more temperately, calls an agenda to "[mediate] between realms of 'high' art and popular sensibility."(Footnote 22) The middlebrow approach owes it emergence to disillusioned "highbrows," professors and reviewers, in the 1920's who considered the elite "genteel" aspirations of the past century undemocratic, yet disdained mass/lowbrow culture for its populism and supposed bad taste. Over the next three decades, middlebrow adherents promoted the growth of book clubs--in particular, the Book-of-the-Month club--literary reviews in newspapers, lectures on art, education-based discussions on television and radio. Articles such as "What Makes Great Books Great" were average reporting fare.(Footnote 23) At work was the belief that ordinary (that is, "middleclass") people could understand the classics, not because they belonged to elite, specially trained literary circles but because (1) they educated themselves using available tools (newspapers, radio, etc.) and (2) they applied their own experiences to great literature. In a 1957 book review, Vincent Starrett assured readers that an "enjoyable, rewarding, and significant library can be formed at relatively small cost by a man of taste and intelligence." It is noteworthy that Starrett dismissed "a First Quarto of The Duchess of Malfi" as too expensive for this library. The Duchess of Malfi might interest a middlebrow reader but not a first Quarto. Starrett's advice is meant for the Everyman, not the wealthy dilettante.(Footnote 24)

The Duchess fit well into the peaking of the middlebrow movement in the 1940's and 50's. Revivals of classics, especially Shakespeare's "contemporaries," were popular. When Thomas Caldecot Chubb reviewed the 1951 publication The England of Elizabeth, he placed the Duchess alongside other classic Elizabethan characters (Volpone, Falstaff), stating boldly, "[T]here are certain brief periods of concentration in which achievements are many and outstanding . . . We all know about [the Elizabethan Age's] mighty drama . . . Certainly it was the most versatile."(Footnote 25) The Duchess became the object of a discussion group; it was debated on radio and television. A gift book of the play--illustrations by Michael Ayrton; forward by director George Rylands--was listed on Gimbels' 1948 full-page Christmas display ad with the tag line "limited editions signed by the artist."(Footnote 26)

The prevalent interpretation of the play (courage in the face of death) also fit middlebrow requirements, being both classical and applicable. As late as 1961, a televised Catholic Hour addressed "Man's dignity in the face of death described in scenes from 'The Duchess of Malfi' by John Webster."(Footnote 27) For nineteenth and twentieth century critics (except, possibly, Brooks Atkinson), the Duchess was the main character (her grandiloquent yet crazed brother served as counterpoint), her increasing trials the central point of interest.

Such a specific interpretation, promoted as it was by the advancement of American middlebrow culture, undermined rather than aided The Duchess' popularity. It is possible, of course, that without middlebrow culture, The Duchess never would have been produced (as a Shakespeare clone) in America at all. Nevertheless, the safe but too strict interpretation of courage in the face of death curtailed the audience's creative involvement.

Application of Votary Theory

We have established context for The Duchess, both its history in America and its treatment in 1946. Let us now imagine an audience member for the play: a young, white woman in her mid-twenties. She has a college degree, unusual for a woman in the mid-1940's but not unheard of. She teaches in a local high school. This will change when she gets married; she will become a housewife and move out of the city into a bungalow in upstate New York. Her soldier fiancé is currently still abroad, but she expects him home shortly. World War II has ended; America is experiencing enormous euphoria. Our spectator's expectations of the future are positive.

Our audience member knows The Duchess is coming to New York. She has followed the reviews. Despite the reviewer's criticisms, she means to attend. Perhaps, she is a fan of Bergner. Perhaps, she is an early proponent of civil liberties. She is pleased that the black actor, Canada Lee, plays the part of Bosola, even though it is a "white man's" role. During the war, her boyfriend served with Negroes; their letters to each other describe the changes they expect to see in American life for blacks and Jews. Consequently, like the actor himself, the spectator considers the casting choice an advance for race relations.(Footnote 28)

Our audience member is also a proponent of middlebrow culture. The purpose of education, she believes, is to familiarize students with great literature. They may not be able to learn everything there is to learn about a work of art, but at least they can be exposed to the canon. Perhaps, she even considers it her duty to attend The Duchess so she can describe it to her students. However, she also enjoys Shakespeare and is aware of the contextual link between Shakespeare and John Webster. The Duchess should be a treat.(Footnote 29)

She attends a matinee on a Saturday, buying a ticket for $2.00; this will place her in the middle stalls. What, we now ask, did she experience? Was it positive? Negative? Was she able to enter the play, find a place from which to enjoy the action? What did she tell her students the next school day?

It is likely, first of all, that she had difficulty entering the play although she may have approved of it. The Duchess in 1946 had been cut to a safe formula--dignity in the face of death--a formula which would resonant with our audience member. Death has been an inescapable topic for her over the last few years; she did not know what would happen to her, her family members or her fiancé. She is sympathetic to the toughness and determination exhibited by the Duchess, who also faces an uncertain future.

Yet, at the same time, The Duchess' formula seems rather inflexible and a trifle dull. Our audience member has read the play. Furthermore, she is an Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers fan. She grew up listening to The Shadow with her siblings. Her boyfriend has a penchant for monster films, although she never cared for them. She does admire Humphrey Bogart whom she saw that summer in The Big Sleep, one of the new popular film noir.(Footnote 30) In attending The Duchess, she expected a bit more, well, gore, to be honest. Excitement. She knows the world is a dark place; she knows what her fiancé has seen in Europe. They don't need to tidy up this play for her. Good grief, she won't be offended or astonished by dead hands and incestuous brothers.

But the dying Duchess never leaves her gaze, never reveals the darkness, subtlety and phantasms behind the producer's interpretation. Any attempt to clamber inside the production is thwarted by the forceful interpretation. Creativity is balked. Our spectator feels as if she were plunked into a Gothic thriller and commanded only to watch the still-life. She is impressed by the sumptuous Elizabethan costumes. But costumes aren't enough. Something more is needed.

Votary theory argues that although context (middlebrow culture, WWII) affects experience, the search for a creative baptism is super-contextual. Alongside defenders of reception theory, votary theory agrees that gaze--looking for creative possibilities--belongs within the individual purview of the reader/spectator. We respond to visual and lingual signs which are grounded in culture and arise from specific contexts; however, our reactions stem not only from historical and cultural attitudes/teachings, they are also deliberate, physiological and creative. Hence, I can enjoy Shakespeare even though I am not an Elizabethan. I can enjoy books by Gabriel Garcia Marquez although I am not Latino. My interpretation, my understanding may change with my context, but my enjoyment, my enthrallment, my desire to enter the play, the text, unbalked, will not.

The audience member brings creative desires to a performance. Once there, creative engagement is encouraged or stultified by the performance. Ellen Esrock of The Reader's Eye discusses various factors that affect the likelihood of visual (or creative) engagement. She quotes from a reader:

For me the text was too exact and definite a description to encourage visualization; one felt as if one is too forcibly being asked to see the [text] as the author wants.Esrock dismisses the first possibility and focuses on the second. Votary theory, however, claims the first as equally if not more valid. The reader is exhibiting a creative desire. Balked from exercising that desire, the reader feels that the text has failed her. Likewise, votary theory argues that spectators (readers) desire creative participation in a performance (text). If thwarted, they lose interest, refusing to take the work in "with lunch" or at any other time.

It is possible of course that my reaction was psychological; the imagery was too negative for me to willingly take it in with lunch.(Footnote 31)

According to votary theory, creative satisfaction is one reason 1946 New Yorkers attended The Duchess. Their classical and applicable needs fulfilled, spectators would still welcome, still seek, entrance into another world. After all, if classical and applicable lessons are all one requires, Cliff Notes and platitudes will do the job. Czinner's production of The Duchess appears, unfortunately, to have fallen short even of platitudinous Cliff Notes.

Rather, our 1946 spectator languished with a too "exact and definite" text. The production confounded her ability to enter the world of the creator, stabilize her perceptions alongside those of the director. Interpretation was a barrier, not an aid. A too fluid interpretation, on the other hand, would have given our spectator nothing to work with, nowhere to sit like entering a house empty of furniture. Furniture abounds in Webster's script; it resembles a Victorian cottage awash with side tables, bureaus and hard little chairs. Paradoxically, an earnestly strict interpretation may be the only way to clear the room. It is likely this dilemma that provoked a 1946 reviewer to describe any production of The Duchess as "an impossible task" due to the "two-dimensional characters moving with obscure motivation in a world filled with violence, lust and brutality and devoid of sense, poetry or tragedy."(Footnote 32)

It is possible, of course, that some spectators did muscle their way into the 1946 production, making themselves part of Czinner's version of Webster's vision. Readers/spectators are individuals with individual tastes; they will find certain worlds more appealing than others; lacking other options, they often take whatever comes to hand. However, considering the play's short run, the votary theorist must ask, Is there any way our 1946 spectator could have been satisfied (or, more satisfied) creatively?

In 1964, John Russell Brown wrote of The Duchess, "The tragedy cannot be said to have had a fair chance in the theatre." Thirty years later, Don Moore, who studied The Duchess' performance from its inception up to 1964, concurred: "But intelligent, sensitive productions of Webster are generally rare in the modern theatre."(Footnote 33) A sensitive production, however, may not have been the answer in 1946. The play has creative possibilities both of horror and ambiguity; both could have satisfied a post-World War II audience member in America.

As Stephen King has proved, horror is an accessible medium for creative needs.(Footnote 34) In fact, horror relies on a reader/spectator who is willing to approach the monster's closet, not alongside the protagonist, perhaps, but certainly behind his or her shoulder. Horror was an available option when The Duchess arrived in New York in 1946; Dracula had opened on Broadway in the fall of 1927 and become an instant and rampaging success, spawning an industry that is still strong today. Shorn of its middlebrow and genteel associations, The Duchess is a kind of Diabolique meets Psycho extravaganza with Freddy Krueger thrown in just for fun. Reviewers before and after The Duchess' 1946 opening described the play (rather than the production) as "blood thirsty," "dark and violent melodrama."(Footnote 35) Advertisements desperately proclaimed the play's sensations; the reporters and marketers knew, if the producers did not, what the audience would look for. As a horror show, rather than a Shakespeare clone, The Duchess may even have morphed its way onto screen á la Dracula--The Aunt of Bosola, Frankenstein and the Duchess. After all, the play offers graveyards, madness, betrayal, abuse, corpses, werewolves, conspiracies, not to mention multiple murders.

The play also offers ambiguities. In her book Dead Hands: Fictions of Agency, Katherine Rowe successfully demonstrates that The Duchess deals thematically with the problems of contractual relationships. The dead hand in the play is a symbol of the connection between intention and act. It ratifies a contract at the same time it binds the wielder to that contract. The issue of free will is continually under examination. Is Bosola, servant to the Duke, an independent agent or an extension of his master, executing stated orders?(Footnote 36) Such problematic relationships, as distilled in the play, could have provided a complex, yet intricately woven world for the 1946 spectator to explore.

The problem of contractual relationships rises out of its time period; The Duchess is a Jacobean play replete with Jacobean themes. Yet issues of self-interest, contractual ties, intent, consequences and freedom exist in our own culture. Nor would these issues have appeared strange to a 1946 spectator. As Americans turned from war to the business of getting on with jobs, marriages and domestic affairs, issues of identity (personal, national, familial) arose. Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman appeared on the American landscape in 1949. Tennessee Williams was producing works at the same time as well as Faulkner and Hemingway, all writers who tackled issues of self-identity and the particular "contracts" that influence that identity.

If our 1946 spectator had been allowed inside The Duchess, she might, like the student of history, have found a place from which to watch the various, complicated connections (between the Duchess, her brothers, Antonio and Bosola) tangle and untangle themselves. In fact, recent productions have stressed contractual issues of class and psychology. Of a 1995 production, a New York Times reviewer stated, "[It's] a sort of Freudian soap opera, a thinking person's 'Dynasty'."(Footnote 37) Perhaps now, more than in the last two centuries, we can explore the tensions between the Duchess--who chooses a lover she never acknowledges--and her brothers--who sacrifice their sister for the sake of money and revenge--and Bosola, who struggles over his agency in a seemingly relentless hierarchy.

By studying The Duchess' reception in America from the perspective of votary theory, we can gain an appreciation of the emotions and pleasures (and disappointments) of a 1946 audience member and possibly, even, a sense of the times in which Webster himself thrived, times filled with uncertainty, aristocratic patronage and a taste for dark, sensational stories. The Duchess (1946) could have utilized the creative options of both horror and ambiguity; instead, the play relied on a strict middlebrow interpretation which held its audience at arms' length, thwarting creative involvement.

This returns us to the main argument of votary theory: people are not motivated principally by socially or politically powered wants. The Duchess in 1946 offered a socially acceptable interpretation; the producers stretched audience acceptance by casting a black man in a supposedly white man's role but, then, the audience, or at least the critics, appeared disposed to be racially tolerant. The Duchess starred a well-known actress, well-known director, well-known composer. The play itself had recently received great acclaim in England. It satisfied certain ideological tendencies in American culture. None of this was enough. The 1946 audience wanted creative access. Without it, they lost interest.

The audience may have been satisfied creatively by an interpretation geared towards horror and ambiguity. After all, it is possible to link a desire for horror and ambiguity to the abrupt social changes and devastating wars of the mid-twentieth century, although such explanations run the risk of creating obsessively tidy schematics. After all, it is also possible that the horror genre of the twentieth century anticipated a need that goes back to Homer and the flesh-eating crocodiles of Egyptian mythology. In any case, although that feeling or need existed in American life, The Duchess of Malfi (1946) failed to provide or access it in a creative fashion.

The Duchess of Malfi still lurks in our culture. Occasionally, I encounter fellow devotees. It is hard to give it up as a lost cause. Possibilities abound. The ambiguous villainy of Bosola would find its popular complement in Spike from Buffy, Anikan Skywalker from Star Wars, Andrew Lloyd Webber's Phantom, Smallville's Lex Luther, the lawyers of Boston Legal. Perhaps, another production will arise which will give us the sensations, the prose, even the dignity, but also allow us entry so we may pleasurably, actively, wander at will.

1. Pepys approved of the first version that he saw; he disliked the second and never attended another showing. Don Moore, John Webster and His Critics, 1617-1964 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 10.

2. Productions of Shakespeare are well-documented: Romeo & Juliet in 1730, Richard III in 1750; Othello in 1751, The Merchant of Venice in 1752. All played in New York with the exception of the last which played in Williamsburg. The Restoration comedies were also performed in America in the eighteenth century: William Congreve's Love for Love in New York in 1750; John Gay's Beggar's Opera the same year, also in New York.

3. Moore, John Webster and His Critics, 11, 15.

4. "Brief Notice," Overland Monthly & Out West Magazine 30 (1897): 94.

5. The articles include "Disease and Death on the Stage" (1893) by the Health Commissioner of New York, in which the Commissioner explains that death does not occur in the dramatic way it does on stage; "Three Dream Heroines" (1889) in which a writer for Scribner's Magazine romantically compares the character of the Duchess to Viola (Twelfth Night) and Elizabeth (Pride & Prejudice). In 1871, Reverend Francis Jacox used a quote from the play to illuminate Proverbs 3:24 for his book Scripture texts illustrated by great literature; that same year, Olive Logan praised the Duchess as "queenly, lovely, accepting death" in her book on the moral effects of playgoing. All articles located at Cornell University and the University of Michigan's Making of America, http://www.hti.umich.edu/m/moagrp.

6. "'The Duchess of Malfi' Revived," Christian Science Monitor, December 30, 1919, 14.

7. Performances prior to Broadway are referred to in Edwin Melvin's "Elizabeth Bergner Starring in Revival of Webster Drama," Christian Science Monitor, September 24, 1946, 5; and Louis Calta's "'Duchess of Malfi' Due at Barrymore," New York Times, October 15, 1946, 39. The Mercury Theatre's change of plans: "Max Gordon Play Will Open Tonight," New York Times, March 21, 1938, 18.

8. Reportedly the two writers did not get along. Bertolt Brecht began the adaptation; Auden was brought in later. Brecht removed all the gory scenes, including the severed hand, stressed the incest and streamlined the plot. It is said that director, George Rylands, upon seeing Brecht's adaptation, was appalled at his removal of all the good bits. Discussed in Bertolt Brecht, Collected Plays, vol. 7, eds. Ralph Manheim and John Willett (New York: Random House, 1974); and, Ian Samson's article, "Malfi mish-mash," Times Literary Supplement, June 4, 1993, 19.

9. Sam Zolotow's articles: "British Director Signed by Czinner," New York Times, August 22, 1946, 40; and "Britten is Writing Overture for Play," New York Times, August 28, 1946, 39.

10. Louis Calta, "The Curtain Falls on the 1946-47 Campaign," New York Times, June 1, 1947, X1.

11. Whitfield Connor, who played Antonio, later signed with Universal. John Carradine, who played the Duke, was already a well-known figure on Broadway and in Hollywood.

12. The Brecht/Auden adaptation was finally put to use in 1998 at the Chelsea Centre Theatre in London.

13. Hotel, DVD, directed by Mike Figgis (2002, United States: Metro Goldwyn Mayer Home Entertainment, 2005).

14. "Classified Ad 9," New York Times, April 5, 1858, 8.

15. "Display Ad 114," New York Times, August 8, 1946, 20.

16. L.A.S., "Canada Lee Takes Role of Bosola In 'Duchess of Malfi,'" Christian Science Monitor, September 30, 1946, 5.; and, Brooks Atkinson, "The Play," New York Times, October 16, 1946, 35.

17. Melvin, "Elisabeth Bergner Starring In Revival of Webster Drama," 5.

18. Brooks Atkinson, "The Play," 35, and Atkinson, "Theatre: Horror Play," New York Times, March 20, 1957, 33.

19. "'Duchess of Malfi' Discussion," New York Times, February 28, 1957, 25.

20. Howard Taubman, "Theatre: A Drama Series," New York Times, March 5, 1962, 27.

21. John Webster, "The Duchess of Malfi," in the Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. 1, ed. M.H. Abrams (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), lines 200-204.

22. Information on middlebrow culture drawn from Lawrence Levine's Highbrow/Lowbrow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988); and, Joan Shelley Rubin's "Between Culture and Consumption: The Mediations of the Middlebrow," in Power of Culture: Critical Essays in American History, eds. Richard Wightmann Fox and T.J. Jackson Lears (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993); and Rubin's The Making of Middlebrow Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

23. Arthur Mizener, "What Makes Great Books Great," New York Times, March 9, 1952, BR1.

24. Vincent Starrett, "Books Alive," New York Times, February 10, 1957, B11.

25. Thomas Caldecot Chubb, "These Made It Great," New York Times, July 8, 1951, 148.

26. "Display Ad 46," New York Times, December 5, 1948, 47.

27. "Television Programs," New York Times, March 14, 1961, X14.

28. Canada Lee performed the role "white face." To modern sensibilities, this seems shockingly racist, yet to Lee, and many reviewers, it was a progressive choice: a black man had been selected to play a (white man's) role for his ability, not his skin color. An image of Lee being made up as Bosola can be found in Monica Z. Smith's Becoming Something: The Story of Canada Lee (New York: Faber & Faber, 2004), photograph insert.

29. I may seem to be stacking the deck here in my image of a 1940's audience member, but in fact, this individual closely resembles my mother and my aunt. My aunt Eleanor attended New York University before World War II. During the war, she was in the WAC. She returned to NYC in 1946 to get her Ph.D. My mother lived with Eleanor in NYC in 1954. My mother later taught grade school in upstate New York (her degree is in art) before and immediately after her marriage; her "boyfriend" was a nuclear engineer, not a returning soldier. My imaginary spectator's politics and opinions regarding literature and race closely resemble opinions expressed by my aunt and my mother.

30. Middle class Americans of the era were not only interested in self-betterment through the classics, they were also fascinated by mysteries and monsters. The popular horror film industry was "profitable cinema entertainment," as a New York Times writer called it in 1936. "Vampires, Monsters, Horrors," New York Times, March 1, 1936, X4. American spectators not only frequented horror films but the more prestigious film noir: Double Indemnity in 1944, Murder, My Sweet in 1945 and The Big Sleep in 1946. Perry Mason, The Maltese Falcon, and The Shadow all aired on radio in the same time period. It was the age of mystery fiction from Nancy Drew to Raymond Chandler. Agatha Christie was a steady British import.

31. Ellen Esrock, The Reader's Eye: Visual Imaging as Reader Response (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1994), 185. This quote also illustrates that despite my reservations over the use of surveys, it is possible to elicit discussions of creative engagement from readers/spectators. I will explore this possibility more in the fourth chapter.

32. L.A.S., "Canada Lee Takes Role of Bosola in 'Duchess of Malfi,'" 5. Regarding the Brecht/Auden script, a recent reviewer commented, "Webster's chaos may be impossible to re-direct." Ian Sansom, "Malfi mish-mash," 19.

33. John Russell Brown, ed., The Duchess of Malfi by John Webster (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1964), lix; and Moore, John Webster and His Critics, 1617-1964, 152.

34. In 1999, I attended a Brown Bag lecture by Stephen King with a friend (a fan of King). I was surprised and impressed by the number of attendees (the talk was moved from the Portland Public Library to the Holiday Inn on Spring Street in Portland), by the variety (young/old/men/women), yet solidly conservative character of the audience.

35. Brooks Atkinson, "The Play" 35; and Edwin Melvin, "Elisabeth Bergner Starring in Revival of Webster Drama," 5.

36. Katherine Rowe, Dead Hands: Fictions of Agency, Renaissance to Modern (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 101.

37. Ben Brantley, "A 'Duchess' Returns, Engulfed by Depravity," New York Times, December 11, 1995, C11.

No comments:

Post a Comment