I need to thank my brother, Dan, for footnote 27. His comment, which I've paraphrased and which he may not remember making, arose over a discussion of the sitcom Roseanne.

***************************************

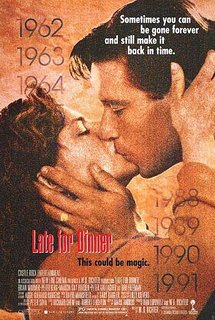

Late for Dinner

Rip’s heart died away, at hearing of these sad changes in his home and friends,

and finding himself thus alone in the world. Every answer puzzled

him, too, by treating of such enormous lapses of time, and

of matters which he could not understand . . . he had no

courage to ask after any more friends, but cried out in

despair, "Does nobody here know Rip Van Winkle?"

"Rip Van Winkle" by Washington Irving

Rip’s heart died away, at hearing of these sad changes in his home and friends,

and finding himself thus alone in the world. Every answer puzzled

him, too, by treating of such enormous lapses of time, and

of matters which he could not understand . . . he had no

courage to ask after any more friends, but cried out in

despair, "Does nobody here know Rip Van Winkle?"

"Rip Van Winkle" by Washington Irving

Votary theory can be applied across time and place: to Homer and Shakespeare, to Tennessee Williams and Faulkner, to New York Times bestsellers and academic tomes, to obscure works and well-known ones. Votary theory is not meant to explain why, or why not, a work has lasted, although that issue may be addressed. Rather, it is meant to provide an approach that places the creative desire forefront in the scholar's mind. With that in mind, I have chosen a popular culture work for this chapter. Too often, the products of Hollywood are dismissed by scholars as market-produced phenomenons, "bread and circuses" dispersed to mollify jaded, unresponsive, uncreative audiences. The humanities scholar should avoid such assumptions. Every work should be examined with the creative desire in mind. In this way, a broader appreciation of artistic works and creative desire may be fostered.

The film Late for Dinner debuted in American theaters in September 1991. Reviewers gave it a lukewarm reception, and it was gone from New York movie houses in less than a month. It is too early, perhaps, to consign Late for Dinner to the well of forgotten and unmissed productions; however, the movie is currently difficult to track down. It does not appear in video catalogs, rental stores or even on-line rental sites, such as Netflix.(Footnote 1)

I have purposefully chosen an obscure popular work since popular works are, to an extent, more than adequately discussed, analyzed and contextualized by their proponents. I do not intend to dismiss or undermine the work of such fans--as, unfortunately, so many popular culture studies end up doing--but rather to defend and underscore the fan approach from an academic angle.(Footnote 2)

Late for Dinner is the story of a 1960's man, William Husband, who, through a series of odd but not unrelated coincidences, ends up with a bullet wound. His well-meaning but somewhat backward brother-in-law, Frank, gives him into the care of an equally well-meaning doctor. Both young men are frozen. When they wake up, through yet another series of coincidences, they find themselves in 1991. The bullet wound has healed, the outside world has changed, and Willy is in the unenviable position of wanting to reunite with his wife, now thirty years older, and his daughter, now grown with children of her own.

The film is sweet and unpretentious. Despite its current lack of popularity, it is not unimaginable that a later generation will rediscover Late for Dinner. At that time, a humanities scholar, using votary theory, might examine how the film was received in the 1990's and whether it was susceptible to creative involvement. I will proceed as that future scholar would. Votary theory should operate in any time and for any work; by examining a contemporary popular work as if through future eyes, we can gauge the theory's effectiveness. Such an approach can also warn us of the pitfalls, the dangers, of any critical theory. We know that we live in complicated times. Will future generations understand this? Or will they be so flummoxed by the extant evidence, they will be tempted to reduce and streamline information in order to make sense of seemingly paradoxical material? If they are tempted, how much more likely are we to suffer from the same tendencies? Consequently, we should be careful in our examination of artistic works, alive to the possibilities, contradictions, aura of any time period. We must use our discernment as scholars, readers and human beings as we probe a work's context and content.

The History Surrounding Late for Dinner

The future humanities scholar would learn that the decade in which Late for Dinner appeared contained many films about time travel: Back to Future's time travel trilogy (1985-1990), Forever Young (1992), Demolition Man (1993). The last two films use the same plot device as Late for Dinner: cryonics, where a character is frozen and then revived many years later. A determined humanities scholar would discover an earlier film utilizing cryonics, Sleeper (1973). A very determined humanities scholar would discover cryonics in 1990 television shows, Star Trek: Next Generation and Star Trek: Voyager.(Footnote 3) Why was the cryonics device so common at this time? Why, since it was so common, was Late for Dinner not more of a hit?

Cryonics made its appearance in the mid-1960's after refrigeration became a widespread and cheap option. Cryonics is, specifically, the freezing of human bodies/heads, rather than the cooling of metal, fuels and food (cryogenics) or the freezing of living tissue (cryobiology). In 1964, Robert C. Ettinger, a Michigan physics teacher, published The Prospect of Immortality, which promoted cryonics as a solution to world problems. Ettinger believed the future would be a Golden Age in which genetic engineering, human intelligence, strength and health would be enhanced, so enhanced that frozen individuals would have to be "improved" (altered genetically) before they woke: "we shall be immediately equal to our descendants," Ettinger assured the reader.(Footnote 4) Due to Prospect, Ettinger is referred to as the father of cryonics in several sources from the late twentieth century.(Footnote 5) While Ettinger may not have formed the scientific underpinnings of later cryonics programs, he definitely formed the underlying psychological justification for it.

After the debut of Prospect of Immortality, societies arose to promote "life extension," among them the American Cryonics Society, Cryonics Society of New York (an outgrowth of the Life Extension Society) and Ettinger's own Cryonics Institute. The best known of these organizations has been the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, started in 1972. Alcor made many media appearances between 1985 and 2000 on Oprah, Donahue, Good Morning America.(Footnote 6) A fervent, almost religious, self-promotion was at work. A 1985 Alcor newsletter stated:

Will all this media hype do us any good? One of us (Mike Darwin) has long been opposed to media exposure of this kind and has been keeping a close eye on the benefits as well as the liabilities of our PR campaign. So far the media work has netted us two suspension members (fully signed up with funding) and put several strong candidates for suspension membership in the pipe. Frankly, this isn't bad for starts. We know that it will take "repeated hits" with our message before anyone seriously considers signing up. We also are beginning to believe that there may be some advantages to "consciousness raising" among members of the public as a result of these stories. Nevertheless, it is hard to do these things. It is hard to be treated like a circus animal and to invest the tremendous amounts of time required -- with so little to show for it in the way of immediate benefits.(Footnote 7)An excerpt which sounds like nothing less than a thoughtful but serious call for missionary work.(Footnote 8)

At first glance, Late for Dinner and similar films appear to function as "consciousness raising" tools for cryonics. However, cryonics was not largely popular in the late twentieth century. The total number of frozen cryopatients in America in 1998 was approximately 100.(Footnote 9) The cost was prohibitive--$50,000 at Alcor per literal head(Footnote 10)--provoking the relatives of a twentieth-century sports star to go to court over his frozen head and the attached bill.(Footnote 11) But if one is searching for evidence of ideological warfare practiced by a dominant group through the use of mass media, it should come as no surprise that the most likely proponent of cryonics in 1998 was a single, white, middle class, agnostic male.(Footnote 12)

Despite the classist, patriarchal, even racist implications embedded in cryonics, it is likely that the appearance of cryonics in movies like Forever Young and Late for Dinner was neither a tribute to nor, as in Sleeper, a satire of the cryonics industry. Cryonics merely provided a modernized "scientific" version of time travel. Time travel itself has a respectable history in film and literature; in American literature, it extends back to Rip Van Winkle.(Footnote 13) Yet, although a subgenre of time travel, the cryonics device was surprisingly short-lived. Time travel without any accompanying sleep or death remains far more popular.(Footnote 14) The cryonics device possesses an intrinsically negative aura as well as a creative deficiency that is reflected in arguments pro-cryonics. When, in Prospect, Ettinger quotes from a doctor of psychiatry that "death can be faced more readily if there is little to lose by leaving life than if there is a great deal to lose," he misses the implications of the good doctor's analysis.(Footnote 15) When we die, we lose the things that enhance our lives, make it familiar, dear, ours. "To die, to sleep," Hamlet groaned. "To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub/For in that sleep of death what dreams may come/When we have shuffled off this mortal coil/Must give us pause." Any sensible person, that is. Ettinger needed to read more Shakespeare.(Footnote 16)

With cryonics, Ettinger and his supporters simply substituted one unknown for another. Ettinger's "sell" of an enhanced, perfected future engendered just as much doubt as any theology of the twentieth century (as cryonics’ status as talk show fodder indicates). Likewise, rather than providing the perfect time travel plot, cryonics proved instead a problematic device, invoking more questions than solutions. This can be seen when we turn to the device as it was received by Late for Dinner's reviewers and as it was handled in the film itself.

Treatments

"Best part of 'Late for Dinner' comes too little, too late," wrote Janet Maslin for her September 1991 review; other reviewers agreed. Although some liked the film, reviewers across the country considered it only a partial success. "'Late for Dinner' isn't Filling Until the End," proclaimed Susan Stark of the Detroit News while Jeff Bahr of Omaha World Herald, more positively, wrote, "2nd Hour Makes 'Late for Dinner' Worth the Wait" and the reviewer for the Orlando Sentinel, while labeling the film "oddly clunky" finished with a snort of praise: "There's a Rip Van Winkle poignancy to [the end] of Late for Dinner that Back to the Future, for all its glossy brilliance, didn't approach."(Footnote 17)

Interestingly, another cryonics-device film, Forever Young (1992) earned similar kinds of reviews: "'Forever Young' Ending is Only Half Thawed Out," Brett Whitlow from the Orlando Sentinel wrote. "After Car Accident, 'Forever' Goes Down in Heap" also appeared in the Orlando Sentinel and Roger Ebert wrote, "'Forever' Flawed--Time Traveling Love Story Suffers from Split Personality."(Footnote 18) Forever Young did better than Late for Dinner (almost $40,000,000 worth). Forever Young's success may be attributed to name stars, Mel Gibson and Jamie Lee Curtis, but the success is relative. Time traveling movie Back to Future made almost four times what Forever Young earned in the United States alone.(Footnote 19)

Like Forever Young, Late for Dinner was promoted as a

romance. "Sometimes you can be gone forever and still make it back in time," the film poster proclaimed (see Fig. 6). The passage of time, due to the cryonics device, enhanced romantic tension. At the end of the film, Willy must convince his wife, now twenty plus years his senior, that their love is eternal. Age doesn't matter. The jacket for the video, released in 1992, declared, "They had a once-in-a-lifetime romance . . . Twice!" while the movie's preview lilted, "All that ever matters are the things that never change."(Footnote 20)

romance. "Sometimes you can be gone forever and still make it back in time," the film poster proclaimed (see Fig. 6). The passage of time, due to the cryonics device, enhanced romantic tension. At the end of the film, Willy must convince his wife, now twenty plus years his senior, that their love is eternal. Age doesn't matter. The jacket for the video, released in 1992, declared, "They had a once-in-a-lifetime romance . . . Twice!" while the movie's preview lilted, "All that ever matters are the things that never change."(Footnote 20)The comparison of Late for Dinner to Forever Young and Back to the Future merits closer scrutiny. Both Late for Dinner and Forever Young, despite their romantic themes (love conquers all) address the issue of loss in a way that Back to the Future does not. Part of this is simply the requirements of the genre: Late for Dinner and Forever Young, romantic dramas, deal with the heroes' separations from their great loves; Back to the Future, a comedy, deals with the hero's separation from his proper time. The subsequent problem--he has single-handedly caused his parents to never meet, therefore causing his own demise--is entirely of his own making. But in Late for Dinner and Forever Young, loss has been forced onto the heroes through the central plot device, cryonics. Neither Willy (Brian Wimmer) or Daniel (Mel Gibson) wants to leave his wife/fianceé. Both suffer from hideous misfortunes that compel them to seek safety in being frozen. In viewer terms, the freezing only lasts a few minutes. In "real" time, Willy is frozen thirty years; Daniel nearly fifty. Their story lines are temporarily abandoned as the viewer speculates who on earth is going to wake these men up and how they will rebuild their lives when they do.

Contrawise, the hero of Back to the Future is never abandoned by the story line; the audience stays with Marty (the hero) as he travels back in time, disrupts his parents' meeting, brings his parents back together and returns to the present. The boy must sleep at some point, but the audience never experiences that event with him (except in the opening and closing scenes). In general, time travel (as used in Back to the Future, Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure, The Navigator and even the outrageous Time Bandits) is more internally consistent than the cryonics device, less prone to break the film's viewpoint, evoking from the audience member outrage and a sense of loss.(Footnote 21)

Like many cryonics-device films, Late for Dinner attempts to solve the problem of the broken story line, broken perspective (however temporary) with humor. After reawakening, Willy and Frank (Late for Dinner) must adjust to modern life. Novelty abounds: ATMs, new music on the radio, medical advances. Likewise, Daniel (Forever Young) contends with answering machines, sippy cartons, and microfiche. Even the satiric film, Sleeper portrays an annoyed Woody Allen giving "historic" (and inaccurate) information to his doctors as he transitions into his new future. In exchange, he learns that sugar and tobacco are now healthy. Later, he encounters incompetent and bored security personnel, silly technological fads, McDonalds, a self-aggrandizing New York arty clique: in Allen's future, not much has changed.(Footnote 22)

In all three films, love fortifies the hero through the transition but unlike the heroes of Late for Dinner and Sleeper, the hero of Forever Young adjusts physically as well as emotionally to his lost years. Over a period of a week, he ages rapidly. When he discovers his fiancée is still alive, he tracks her down. By the time he reaches her, he is a 70-year-old man, the age he would have been in the ordinary course of time. In this case, the cryonics device has a thematic logic that time travel would not. Time travel would not explain why Daniel needs to age before the reunion can occur. His (unnatural) death has placed him, as it did Rip Van Winkle, in a foreign and unfamiliar world. In order to regain balance, he must grow old.

In comparison, Willy (Late for Dinner) adjusts rather easily to the time change. The cryonics device supplies no tension until the end when his wife resists the possibility of reunion. She is too old, she complains. "I wish," Willy replies, "I was to blame for every laugh line on your face." His arguments succeed. The lost years are overcome. Remarriage occurs. The cryonics device is not really necessary; any device (time travel, de-aging pills) could have created the same problem of an older woman wooed by a younger man.

Forever Young, so different from Late for Dinner thematically, was probably not intended as a discourse on the merits of aging. It is more likely the hero's aging was an attempt to conquer the intrinsic problem of the cryonics device. For the device contains so many problems, both thematic and plot-related. In a 1999 Star Trek episode, the ship's crew revives a group of aliens who entered stasis during a war which they partly began; 900 years later, they are still violent, paranoid and angry due to their out-of-date technology (which leaves them vulnerable). Eventually, Voyager's captain refuses to help them, explaining, "I can't ignore history."(Footnote 23) Rather than obliterating the problems of the past--wake up a new and improved individual!--the cryonics device makes the past all too present and problematic. It must still be dealt with; without the intervening years to build on, the task of living (like the audience's involvement) appears a futile one.

Votary Theory Applied to Late for Dinner

Votary theory can be applied to a variety of works. In all cases, the votary theorist must place a work within its historical context and investigate how it was treated without losing sight of the individual's creative desire and, for that matter, the scholar's own creative instincts. The last stage of votary theory is, in itself, an imaginative act. The scholar must hypothesize a spectator/reader. The scholar can, as with The Duchess, develop a likely candidate based on biographical information; the scholar can, as will be attempted in this chapter, create an imaginative inner dialog; the scholar can also, as will be attempted in the next chapter, analyze multiple reader comments in order to reach the likely conclusions of a single reader.(Footnote 24)

Who might have seen Late for Dinner when it appeared in theaters or on VHS? Women of the twentieth century reputedly watched romance films more than men. However, cryonics was favored by men more than women.(Footnote 25) Let us imagine a male spectator; he is thirty-six years old, a computer programmer, married, currently childless. He and his wife watch Late for Dinner on video in 1993. Does he enjoy it? Does he try to enter the film? Once inside, how might the realization of his creative desire sound? (Footnote 26)

The story is not difficult to enter. Much of the plot employs a single point of view, that of Willy who has a great wife (Joy), a great best friend (Frank) and a cute kid. Willy's home is under attack by an unscrupulous developer. The film's somewhat slow beginning introduces the viewer to Willy's friendly home environment; the recognizable threat (big, bad business guy) gives the spectator time to settle inside the story. He tags along as Willy and Frank drive off to confront the corporate bully and shakes his head over Willy's multiple responsibilities. Man, life can be a drag sometimes. At least, Frank is having fun, but Frank is a handful as well as being a bit not there developmentally-speaking. Here's Willy--trying to do the right thing, trying to take care of people--the spectator rather respects him and doesn't mind hanging out with him at all. He sticks with Willy even after Willy is shot; he stays with him all the way from Sante Fe to Pomona. Personally, he, the spectator, would go home right now; he thinks Willy is stupid to be running away since Willy didn't do anything wrong. But Willy is a stand-up guy, a good guy, so the spectator won't ditch him yet.

Cryonics enters the story. The wife sighs and whispers, "Oh, that is so unlikely," but hey, cryonics can happen. Still, it's a good thing Willy is unconscious because a stand-up guy wouldn't abandon his family like that. It's Frank's decision and Frank is, well, a bit slow. At least in that gushy, chick film the wife dragged you to in December--Forever Young--Mel Gibson thought his fiancée was dead before he agreed to be frozen. Besides, it was Mel Gibson--Mad Max, Lethal Weapon--and he wouldn't run away from life.

Anyway, Willy and Frank are wrapped in tinfoil, stuck in tubes and stored away. Everything goes dark. And suddenly, you're on your own. The next scene is some guy in a tractor trailer, but you don't know this guy, and you're not going to hang out with him, which is a good thing because his only job is to crash into the lab, knocking over the tubes and bringing Willy and Frank back to life. Okay, now things are back on track, but what the hell, first you're one place, then you're nowhere. The guy you actually identify with is dead. Yeah, okay, you've got a sentimental side, you'd like to see Willy get back to his wife so you'll give the rest of this movie a chance. Still, that scene change was just weird.

After that, it's a hundred jokes you've seen before about time travel. Yeah, yeah, Michael J. Fox did all that in Back to the Future. Some of the jokes are funny. But what you really want to know is what this guy is going to do when he gets home. Is the jerk who shot him still around? Are his kid and wife still in Sante Fe? Willy and Frank are back in the car now. You're concerned because Willy doesn't know where his family is and frankly, yeah, that would stink. You keep watching the road because in every other movie you've seen, the bad guy drives up about now and starts unloading both barrels. But this isn't really that kind of movie. Remember, the wife chose it.

"I bet the wife is dead," you tell the wife.

"Oh, no, she's not," the wife says.

But she could be. Everything could be different. You don't think anyone will be waiting for this guy, not really, not after thirty years. Maybe, he should just keep driving, skip Sante Fe and head for Houston or turn around and go to Vegas. But there's Frank to worry about, what with his kidney trouble and all, and maybe it's best for Willy to find out what's happened to his family so he can move on.

Turns out Willy's wife is still around. And currently unmarried. And Willy still loves her--"That's so romantic," the wife sighs; you point out that Willy's wife is pretty hot, even at fifty-five, and the wife punches you. But you're starting to worry about Willy, like whether or not this guy is going to be able to get a job. It's great that the wife has kept the family business and gotten rid of the bad guy, but where does that leave Willy? What's he got to say for himself after all these years? He was a milk man at the beginning of the movie, and now his wife collects art. Does he end up working for her? Does he go back to college? The wife is well off as is the daughter, so money shouldn’t be a problem. But Willy isn’t the type of guy to sponge off someone else. He’d want to get a job pretty quickly.

"It's not very realistic," you point out to the wife, who replies that movies don't have to be realistic. ET wasn't realistic. The cryonics stuff didn't make sense, but that was just a way of moving the movie forward.

You point out for the twenty-billionth time that people used to think heart transplants were impossible; science will figure out cryonics sooner or later. Besides, that isn't what you mean. The beginning and end of the movie should go together. So if there's a guy with a gun at the beginning, there should be a guy with a gun at the end.

"Well, it should make sense internally," the wife agrees, "like magic in fantasy stories is supposed to work by certain rules and if it doesn't, the story fails." The wife reads a lot of Tolkien and is apt to make comments like this; you happen to agree this time so you don't roll your eyes. What you're thinking, though, is that Willy died, but usually when people die in movies, they come back to something totally different. Take 2001 for example--

But the wife doesn’t want to talk about 2001 which she thinks is the most boring movie of all time. And anyway, she thinks it is possible for people to get back things that they have lost. But then the wife goes to church.

In any case, what matters to you is that the story should make sense, have closure. Like Back to the Future where Michael J. Fox returned to where he started. Things had changed because of what he did in the past, which made sense--the beginning and end fit together. That's what a movie is supposed to be like. And it has to be entertaining. You really don't see the point in watching a movie that makes you worry about all the things in life that can get you down. There's enough of that in real life.(Footnote 27)

Still, Willy did get his family back. And it isn't like he doesn't have a social security number. As long as nobody looks too closely at his birth date--besides, he could always tell people that he got plastic surgery. So you don't mind Late for Dinner's happy ending, even if it didn't match up to the beginning. You might watch it again on a cheap rental night.

From this scenario of an imaginary spectator, we can achieve some understanding of the creativity of the (male) spectator in twentieth-century America. That creativity was not at the mercy of current trends. Although socially relevant in the twentieth century, cryonics did not translate into viewer popularity. Viewers showed a very human--but extremely irrelevant--preference for older narrative techniques, such as time travel.

There are strong creative explanations for this preference. Unlike time travel, cryonics forces a moment of disengagement. The spectator is abandoned by the main character to an unfamiliar environment. The device also raises too many uneasy speculations: What has been lost in the intervening years? Can the losses be regained? Should they be regained? How much change is too much change? Isn't it always better to stay and sort things out?

Postmodernists insist that contemporary audiences revel in unanswerable speculations. A postmodern work presents a multiplicity of voices, a pastiche of signals that cannot be faced or grasped. Rather than relying on the traditional narrative structure, audiences turn to non-closure.(Footnote 28) There is a political side-effect to postmodernism. By preferring non-narratives to closed narratives, audience members indicate their appreciation for the subversive; they have successfully resisted the forms of the dominant culture.(Footnote 29)

Like so many critical theories, postmodernism seems to be based mostly on academic wishful thinking, a desire that "transgression" be as "important a value" to artists and audiences "as it is for many theorists."(Footnote 30) Even if every work could be deconstructed, reduced to a pattern of symbols and systems, that doesn't mean audiences will like it. When the cryonics device disrupts a film's flow, it scatters the narrative. The uncertain success of both Forever Young and Late for Dinner, as well as the critical reception of both films, indicates a traditional, even orthodox demand by twentieth-century audiences that a story be a complete story, not a collection of bits to be endured. Creative involvement is encouraged, rather than subordinated, by the wholeness of a work's structure, or shape.(Footnote 31)

Through studying Late for Dinner in its context, particularly the treatment of cryonics in the late twentieth century, yet keeping our eye on the possibilities of creative involvement, we can learn something about the issues surrounding not only the film but creativity itself--what it means to be creative, how creativity is satisfied, what creativity involves as well as its importance to spectators/readers. Votary theory hopes to promote such questions in the humanities, to encourage a scholarly and human understanding of artistic works which includes creative excitement and appreciation. The issue, for us in the humanities, is not how much resistance a work may or may not encourage but, rather, in what ways (if at all), creative desires are gratified. Issues of sociological and cultural significance--Is cryonics gendered? Has Hollywood overtaken American culture?--should be left to other disciplines.

Late for Dinner is a respectable, sweet film that won a certain level of acclaim but has since drifted into obscurity. Perhaps, a future generation will rediscover the film and ponder its significance in the context of cryonics, religion, Woody Allen, and postmodernism. They will hopefully discover that twentieth-century spectators enjoyed fantastic films as well as films with seamless narratives. Like spectators of all generations, twentieth-century spectators enjoyed films that provided generous room for creativity and fun. Should future scholars pry further, however, they will discover something much odder than freezing (just dead) people or hurtling DeLorians through time. Within the culture of the twenty and twenty-first centuries, they will discover a fear of creativity, a fear, even, of fun, a fear that not only is mass/popular culture dangerous but that all art is fundamentally unreliable. Theorists attempted to control artistic works with jargon and theory. They ultimately failed. Why, future generations will wonder, were our ancestors so scared?

1. Netflix, http://www.netflix.com. About eight years ago, I was able to obtain a VHS copy at a local video store sale for $5.

2. I will attempt to combine scholarly and fan responses in Chapter 4.

3. Cryonics shows up in a number of Star Trek episodes, including the famous episode "Space Seed" that led to the equally famous movie Wrath of Khan.

4. Robert C. Ettinger, The Prospect of Immortality (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1964), 149, 156. Ettinger believed that future generations would be so advanced, they, unlike us, would consider Shakespeare's language puny and obsolete.

5. Alcor, http://www.alcor.org; American Cryonics Society, http://home.jps.net/~cryonics/; The Cryonics Society, http://www.cryonicssociety.org/.

6. Alcor, http://www.alcor.org.

7. Ibid.

8. Resonating with this missionary/marketing zeal, The Cryonics Society's web site lists "Six Reasons to Join The Cryonics Society Today" while the American Cryonics Society's web site promotes "13 reasons to join."

9. W. Scott Badger, Ph.D. "An Exploratory Survey Examining the Familiarity With and Attitudes Toward Cryonic Preservation," Journal of Evolution and Technology, December 1998, http://www.jetpress.org/volume3/badger.html. See note 12 below.

10. Philip J. Hilts, "With Cryonics, Hope Runs Ahead of Reality," New York Times, July 9, 2002, D4.

11. Tom Verducci and Lester Munson, "What Really Happened to Ted Williams?" Sports Illustrated 99 (2003): 68.

12. In 1998, Dr. W. Scott Badger, an advocate for cryonics, performed a survey to discover why cryonics hasn't had the success its supporters think it merits. He discovered that "[m]en . . . had, for the most part, more positive attitudes towards cryonics than women." He adds that cryonics is favored by "male agnostics and atheists" who tend to be "fairly well-educated" and "between 35 and 64 years of age." In a delightful piece of guilelessness, Dr. Badger goes on to quote from a fellow advocate that "consumers are not attracted to cryonic services for the simple reason that there is no convincing evidence that cryonics will work." From "An Exploratory Survey Examining the Familiarity With and Attitudes Toward Cryonic Preservation."

13. The story of Rip Van Winkle bears a marked similarity to the cryonics plot: a man sleeps and wakes, disoriented, to a different time period.

14. Frequency (2000); Kate & Leopold (2001), Dr. Who and Quantum Leap (TV).

15. Ettinger, Prospect of Immortality, 145.

16. This lack of imagination extends to Ettinger's picture of unbroken social and economic structures between the present (1960) and the future (2200+). Even Star Trek, that ever optimistic science fiction drama, postulates a third World War, mass destruction of all major countries and a generation of feudalism before star travel creates the perfect future.

17. Janet Maslin, "Best part of 'Late for Dinner' comes too little, too late," Minneapolis' Star Tribune, September 23, 1991, 8; Susan Stark, "'Late for Dinner' isn't Filling Until the End," Detroit News, September 20, 1991, F2; Jeff Bahr, "2nd Hour Makes 'Late for Dinner' Worth the Wait," Omaha World-Herald, September 23, 1991, 29; "What's New Movies," Orlando Sentinel, May 1, 1992, 29.

18. Ebert, Roger, "'Forever' Flawed Time-Traveling Love Story Suffers from Split Personality," Chicago Sun-Times, December 16, 1992, 47; Brett Whitlow, "'Forever Young' Ending is Only Half Thawed Out," Orlando Sentinel, December 18, 1992, 30; Andrea Passalacqua, "After Car Accident, 'Forever' Goes Down in Heap," Orlando Sentinel, January 8, 1993, 24.

19. Internet Movie Database, box office and business data for each movie, http://www.imdb.com.

20. "Late for Dinner," preview at Video Detective, http://www.videodetective.com.

21. The broken story line is a bigger problem than it might appear on paper. Many of the stories I write include two perspectives. If I jump too often between perspectives, editors tend to get upset, informing me, for example, that "the only real problem . . . was that the viewpoint flitted about so much that it was hard to get attached to a character and their situation before it changed" (Leading Edge's response to "The Weight of Light").

22. Sleeper, dir. Woody Allen, VHS (United Artists, 1973).

23. "Dragon's Teeth," Star Trek Voyager, DVD (Paramount Studios, 1999).

24. This is similar to the survey option I criticized in Chapter 1. I consider it a problematic approach. In the case of The Last Promise (next chapter), however, the comments are unsolicited, in non-survey form.

25. Dr. W. Scott Badger, "An Exploratory Survey Examining the Familiarity With and Attitudes Toward Cryonic Preservation."

26. Again, surprisingly enough, I'm not loading the deck. On Amazon.com, out of 20 customer reviews, three very positive reviews of Late for Dinner were written by men.

27. I borrowed this sentiment from one of my brothers.

28. This type of postmodern response is described in Susan Bennett's Theatre Audiences: A Theory of Production and Reception (New York: Routledge Press, 1990), 77-78; also, Chandra Mukerji and Michael Schudson, eds. Rethinking Popular Culture: Contemporary Perspective in Cultural Studies (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 47-48; and, Tania Modleski, "The Terror Pleasure: The Contemporary Horror Film and Postmodern Theory," in Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. Tania Modleski (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1986), 161.

29. "At the extreme [of critical theory]," Dana Polan explains, "narrative becomes [for postmodernists] not one of the forms through which ideology works but the only form that ideology ever assumes." Consequently, resisting narratives from the dominant culture becomes the ultimate sign of resistance. Dana Polan, "Brief Encounters: Mass Culture and the Evacuation of Sense" in Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. Tania Modleski (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 170, emphasis in text.

30. Modleski, "The Terror Pleasure: The Contemporary Horror Film and Postmodern Theory," 164.

31. In her commentary on an Angel episode, script writer Jane Espenson remarks that the writers don't need to worry too much when they make mistakes regarding internal consistency since the fan base will do the extra work of figuring out how the "mistake" fits into the whole. ("Rm w/ a Vu," Angel, DVD, Paramount, 1999, commentary.) Rather than indicating an ease with discrepancies, this behavior illustrates a desire to create complete, consistent imaginative universes.

No comments:

Post a Comment